Introduction

Tasmajdan Park (colloquially called Tash) is the second largest park located in the very heart of Belgrade. It’s so central, that you’d have to be as disoriented as a blind lesbian in a fish market to miss it. In the past fifty years, it has become one of the all-time favourite playgrounds of the capital and a popular gathering, leisure and recreation spot. As was the case with other parts of Serbia, the long, interesting and, at times, peculiar history hasn’t bypassed Tasmajdan either.

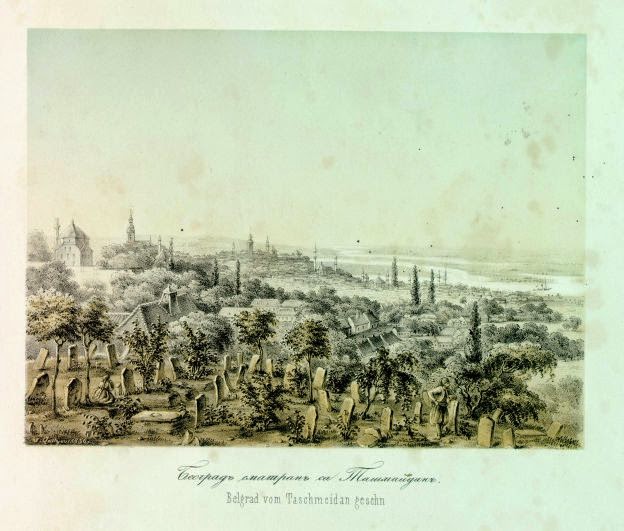

The name of the park and its neighbourhood is of Turkish origin. The “word taş“ means stone, whereas “maden” means a pit, so Tasmajdan is really nothing more than a loanword for a quarry. Indeed, Tasmajdan has been the main extraction point of stone used in the city, and later on saltpeter as well. Natural tunnels in rock have served as shelters to both citizens and authorities, or as storage rooms and hideouts.

Turks were not the first to discover this abundant source of building materials. Namely, Tasmajdan has been in use for at least two millennia before their arrival – since Roman times. The limestone from Tashmaydan is the building block of practically all sarcophagi, which are scattered around town, and every single stone built into the Belgrade Fortress was dug and shaped here.

Tasmajdan History

The space Tashmaydan lies in, was merely an outskirt of a small borderland city up until the XIX century. It was a witness to many tumultuous historical events, that Belgrade was never short of…

For one thing, there is the connection to Saint Sava. The works and life of Saint Sava have been deeply rooted into Serbian national being and his remains were kept as a relic in Mileševa Monastery. When Serbia was conquered by the Turks, a certain Grand Vezir of Albanian origin, Sinan Pasha, decided to defile this sanctity and publicly incinerate the relics on the tallest hill in Vračar. The oral tradition purports the act aimed to humiliate and vanquish any hope that the conquered Serbs had left. It’s more likely, however, that he was seeking to prevent potential future rebellions, as the whole of Banat under Turkish rule was literally aflame with civil uprisings at the time.

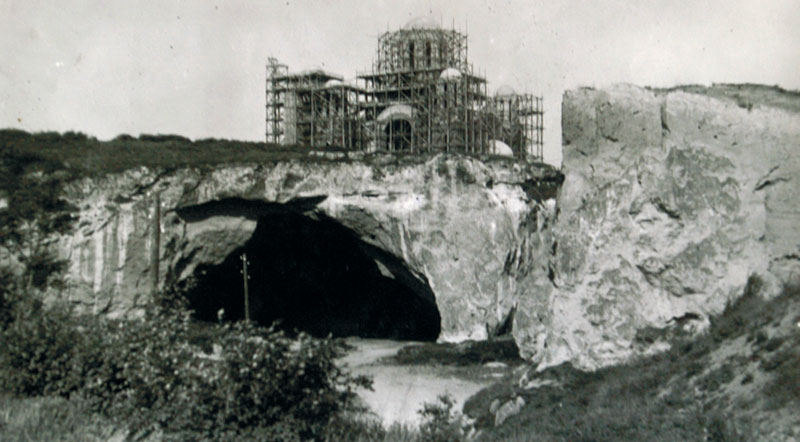

Four centuries later, as a symbol of remembrance, the Serbs have built one of the largest Orthodox Christian Temples in the world on the tallest hill in Vračar to commemorate the event. However, it turned out that todays Vračar, is not the spot where Sava’s remains were burnt.

In 1895. The Temple Building Society actually chose a semi-random location. It seemed like a logical and practical solution and it corresponded to the hill from which the bonfire could be seen by the whole town. Since then, however, several researchers have posited that in Sinan’s time, Vrachar glade was much further away from what is known as Vrachar today.

One of them was Mr Sreten Popović who compiled numerous historical records, to resolve the mystery. He has suggested that Tasmajdan of the times was the location of the Imperial Road – the Road to Istanbul.Historical sources noted that Sinan Pasha placed the stake, so that the city inhabitants and the rebels across the Danube could see it and the only real high-ground near the city gates was the one on Tasmajdan. Moreover, Laudon’s war plans from 1738 mention Vračar Hill as the tallest spot on the outskirts of the city. That hill was between the echelons of Turkish and Austro-Hungarian armies, and it also points to Tash.

Popović explained that the Gypsies who travelled in the area, used to settle temporarily on the side of the Imperial road, as the Turks weren’t particularly keen to let them into the city. They would do small repairs, make mangers, resell horses and engage in petty thefts. Their women, would stop the passers by to do fortune telling and witch-crafting, which is called vračanje in Serbian. Hence the name Vračar.

Vračar’s “dispersion” towards the south seem to have occurred in the centuries that followed. This theory seems plausible, because Tashmaydan leans on today’s Vrachar. Is it truly the place where Sava’s remains were burnt? Well, nobody has proved with utmost certainty, but most of the data points in that direction.

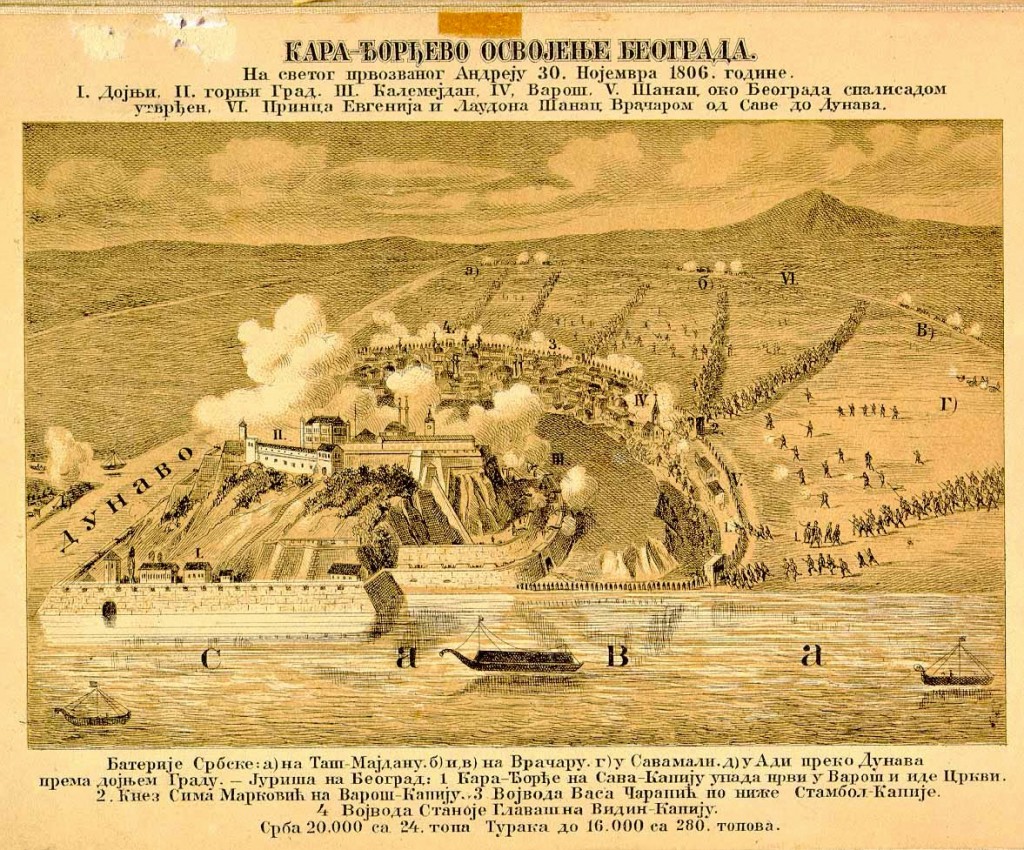

During the siege of Belgrade in 1806. Karadjordje and his 3000 rebels have set a camp in Tashmaydan. Soon after, Karadjordje became a nuisance so, according to the old Serbian tradition, we got rid of him. This unfortunate little event, prevented him to see the results of his own and later on Milosh’s battle on Tashmajdan. In the close vicinity of the park, near Batal-Mosque (today near the building of Parliament), was the place of the public proclamation of hatt-i sharif with the official ferman of sultan Mahmud II. This decree gave Serbia autonomy and the status of vassal state, and ascended the cattle trader, Milosh Obrenović, to royal heights.

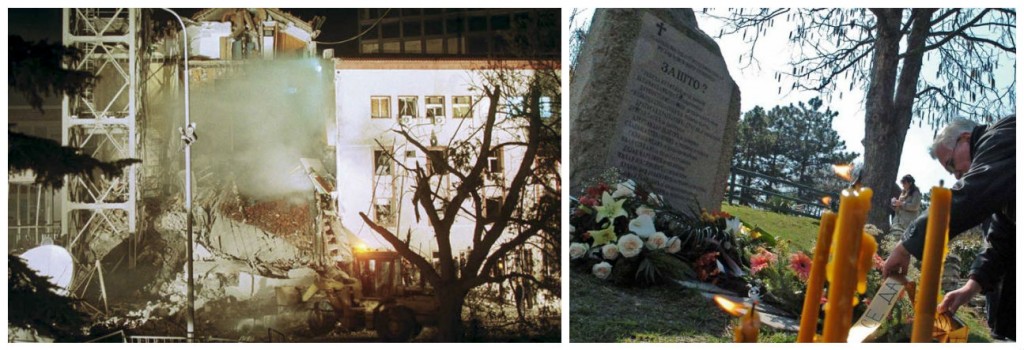

The more recent history of Tashmaydan notes the war waged between NATO alliance and Federal republic of Yugoslavia in 1999, as one of its toughest moments. During that sinister year in Serbian history, the Serbian Broadcasting Company building, in Aberdareva street which is on the northern entrance to park, was blown to smithereens. On the pretext of turning a state run television into a legitimate military target, NATO has successfully managed to kill 16 members of the technical staff, while the TV director and people responsible for dreadfully stupendous propaganda, eluded the moment in the safety of their homes (they basically knew it was coming and left the people inside as scapegoats). The building was demolished, and the pressure of the explosion has turned the inside of the neighbouring children theater Duško Radović to rubble. As an homage to the victims, a small memorial was erected on the parks entrance.

Tasmajdan Graveyard

Millenia of incessant wars have turned Serbia into a land of Calvary, and its history is one long history of (mass) graves. Belgrade, from its early beginnings was made to be a strategic fortification. Its main purpose seems to have been one of a killing field for the numerous armies which fought for the interests of powerful empires, rather than a peaceful spot for family life. Since the times it was called Singidunum until the late XIX century, Belgrade was exclusively a war town, and its most distinctive “brand” was the battle against conquerors. As such, it was always covered in graves, and the number of people in the graveyards has always outnumbered the living at least tenfold (which is why, in the event of a zombie apocalypse Belgrade is the last place you’d want to be). Since the late 1800s however, as the needs of the city changed, the population and demographics have also changed, quite dramatically. As Belgrade grew, most of the city’s graveyards had to switch places.

Before it became a Park, Tasmaydan was one of the largest graveyards in the city. Back then, it was named the New Graveyard, because it happened to be new at the time. Following that train of thought, when the graveyard was moved from Tash to the space encircled by Ruzveltova and Northern Boulevard, Belgraders were bestowed with a new “New Graveyard”.

In the period between the end of 17th and beginning of 19th century, the departed members of the community of non-Turkish origin were burried along and around what is today Brankova street (the one leading from the tunnel leading to Branko’s Bridge). It was Knez Milosh, who issued a decree in 1828, which granted Christian populace of the capital to bury the remains of their loved ones in Tash. An alert and avid researcher needn’t put much effort into finding remains of tombstones, as there is one right next to the building Seizmological Institute. Funnily, this macabre token of past times fits quite well into the surroundings. The gleaming white color ennobles the patch of grass it’s on without a slightest hint of it being what it really is – a part of someone’s grave.

For today’s standards Tashmaydan graveyard was peculiar, to say the least. There were really no official records of burials that took place there. Data was available, but it was confined to the local chaplain – he knew the names of the deceased by heart. It was not a rare occurrence to have the tombstones taken out of the ground, just to have them “recycled” into new ones. The graveyard pretty much resembled an abandoned forest that was randomly picked as a burial ground. In 1880, the local newspaper of the times Videlo, used the phrase a place with absolutely no piety for the departed to describe it. There was a part of the graveyard that was slightly more orderly – the one next to the church. This bit was reserved for the wealthier class and their graves were maintained and properly designated.

The same nonchalant attitude towards the dead was displayed in 1886, when the New Graveyard in today’s Ruzveltova was established. The plan was to transfer all the remains from Tashmaydan to a new location. In a very common course of things, the wealthy and reputable individuals were moved in no-time, whereas the rest took a tad bit longer (most had never left the park). Of course, as most other unpleasant shit in our history, the whole matter was elided (or retold under one’s breath), and soon forgotten.

They say that the most cheerful time in Tashmaydan graveyard was during the church festivity – St Mark’s day. The whole area would be cluttered with tents and improvised sheds. The people would put on their best clothes and celebrate. The whole graveyard would resound with music, the youth would exchange coy glimpses and dance a joyful kolo between and around the tombstones. This festival would last for several days and the occasion showed the weird relationship our ancestors had with their dead. Many would agree that there was something strong, ancient and discernibly pagan tagging along after the Serbs, in the not so distant past.

Tasmajdan Underground

The back side of Tashmaydan, the one facing Ilije Garasanina street, contains entrances to the underground caves beneath the park. In the past two decades, the public interest for caves and mines underneath Belgrade was sparked by a group of enthusiasts from the Speleological Association. Two , who were widely quoted within this text, are Mr Zoran Nikolić and Mr Vidoje Golubović. Owing to their efforts, proper guided tours to these places are organised from time to time (their facebook page is here), as they’re otherwise unavailable to public eye.

One of the entrances into the underground, is from Aberdareva Street, opposite the TV station. The remaining entrances are above and below the Tashmaydan stadium, in the six million year old limestone.The traces of the existence of the quarry can be seen in practically all walls in the underground caves. The regular shape of the arches and holes in the wall stand as a proof of a centuries old stone mine. The historical sources claim that the Serbian authorities, since the beginnings of Milosh’s rule, up until the German occupation, paid a lot of attention to exploring and planning potential strongholds beneath Tashmaydan. Needless to say, the caves served as shelters on numerous occasions and especially during the 1915 and 1941 bombings.

During the Second World War, the Nazis have appropriated, strengthened and enhanced the catacombs and used them as a shelter of the Command center for South East and for the Gestapo. The sheer number of “wormholes” in the ground beneath the Tashmaydan park is so big, that’s practically impossible to conclude who, why and when may have drilled them. Without extensive research, that is, which has been eluding our means for decades. According to some sources, the sports center Tashmaydan is much smaller than the original plan envisioned, because of the numerous cavities in the stone beneath it. The size of the originally planned leisure center would increase its mass to the extent that ground underneath it would collapse.

Many underground passageways have been walled off as a safety precaution, and many are probably still unknown. One of the caves which are still accessible, right underneath the stands of Tashmaydan stadium has a number of large mysterious corridors. The walled off passages lead in all directions and their destinations remain in the domain of speculation. There is one corridor supposedly leading to the building of the Faculty of Law and another in going in the direction of the Old palace in Pioneer’s Park. The mere assumption of the archaeological and tourist wealth this underground world would present is amazing, but the will and the funds to open it are lacking. In 1994 an idea of extensive research of Belgrade underground gained quite a bit of momentum, but got abandoned for the aforementioned reason.

Tasmajdan Churches

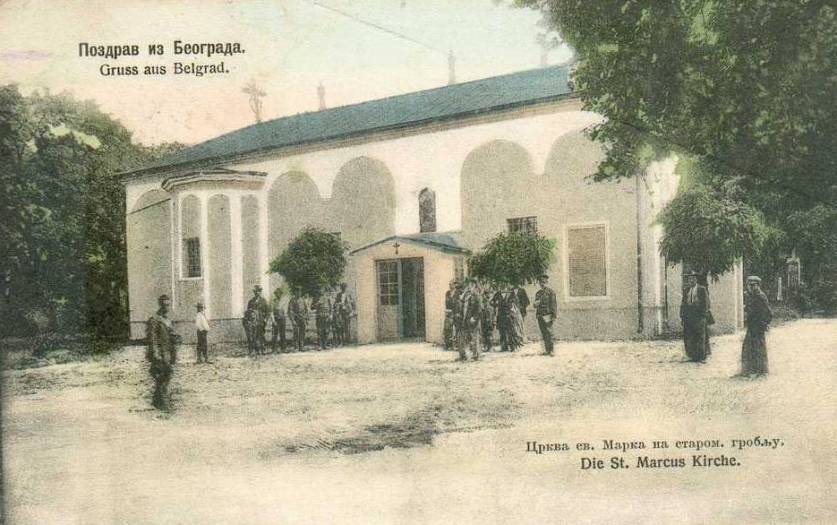

On the right side of what is today St Marko’s Church used to stand a small shrine and its namesake. It was also called Palilula Church. Some theories go on to say that Belgrade authorities wanted to mark Tašmajdan as a place where St Sava’s relics were burnt, but did not want the Turks to figure out their intentions. They decided to find a “replacement” for Sava, in the form of Saint Marco and devoted the church to him.

The church was built by Knez Milosh Obrenovich, with the generous financial contributions from the trader Lazar Pancha in XXX, just to be demolished in 1942 because it was severely damaged by the fire during the April bombings in the preceding year. The remains of King Alexander and Queen Draga Obrenovich and other royal and ecclesiastical dignitaries were then moved into the new church.

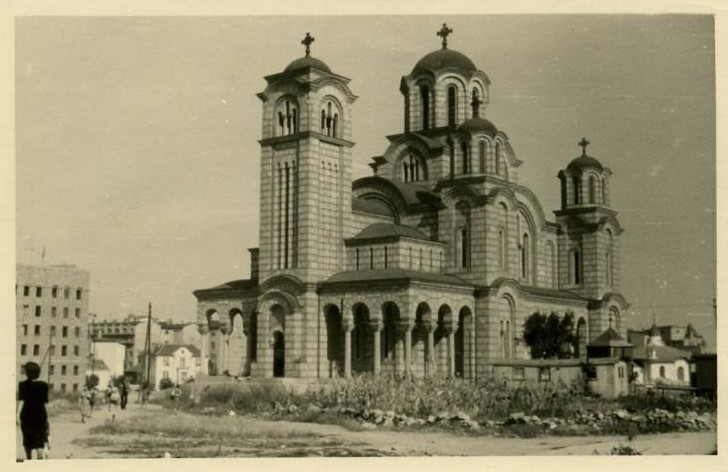

The new church of the Holy Apostle and Evangelist Marco was built between 1931 and 1940. It was the work of two architects, Branko and Petar Krstich, who found their inspiration in Gračanica Monastery. As the church’s power and influence had steadily declined after the second world war, so were the usual decoration of church interior left out. Ventilation, frescoes, lights and sound system are still missing and no one can tell with certainty whether they’ll ever be there. The church today holds the tombs of the members of the Obrenovich dinasty, a couple of epsicopes and bishops, patriarch German, and of the benefactor of the old temple Mr Lazar Pancha. Moreover is also became the resting place of the greatest medieval ruler of Serbia, Emperor Dushan the Mighty.

Just behind this grandiose temple is another Christian Orthodox church – a Russian church of the Holy Trinity. After the October Recvolution, quite a few members of the Russian nobility had fled to Serbia. This architectural symbol of friendship between the two nations was embodied in 1926 (according to Valery Stavesky’s plans) and a clod of Mother Russia’s turf was laid in its foundations.

Tasmajdan kafanas

Belgrade’s recent history is inextricably tied to kafanas which used to be the hubs of social and more often than not economic life of Serbia. Tašmajdan happens to host two of them, Madera and Chance, and they both share a special place in the hearts of Belgraders.

The garden of the Madera restaurant is, in its most part, on the territory of Tasmaydan park. Once, it was one of the most famous kafanas in Belgrade mostly because of its clientele. Its predecessor was also a kafana, called Smederevo, in a considerably smaller building, which was later torn down. The one standing here today was built in 1937, and the ground floor also gave way to a kafana which was named Madera. It is said that one of the guests once brought wine from the Portugeese island of Madeira, and the owner liked the misheard version of the name.

After the Second World War it was a favourite gathering spot of players and high officials of the Red Star football club, who made a private arrangement with the owner to get discount for meals there. Some of the regulars in the restaurant were Dragoslav Sekularac, interanationally acclaimed actor Ljuba Tadić and a bunch of famous journalists.

Today, there are not as many footballers and the overall atmosphere has changed in step with the times. Although regular people drop in from time to time, MADERA is mostly frequented by the elite, whose lifestyle and shoe design blend into the exclusive interior of the restaurant, with its subtle touch of Paris, New York and London.

Poslednja Šansa (Last Chance), today just Chance, was a popular gathering spot of youngsters – especially of those from the Fifth Gramar School in Belgrade and the freshmen of the Faculty of Law. If the assumption that St Sava’s relics were burnt in Tashmaydan is right, then it’s most probably the spot where the Chance stands today. The name because it was literally the last chance for a drink – it was one of the very few places that worked around the clock in the 1960s. Hence it got had a quite a bit of regulars among the urban youths in the period between the 1960s and 1980s. Funnily, at the time of writing of this text, Chance is undergoing its second refurbishment in its 50 year of existence. This time it’s being enhanced even further, and should serve as a sort of a VIP lounge for the stadium.

Tasmajdan Seismologic Institute

Seismology in Serbia came to prominence as a discipline after the great earthquake that happened in 1893. In 1906, the Council od the Faculty of Philosophy of Belgrade University decided to build a special building at Tashmaydan (Tasmajdan) for the Seismological Institute which became the first full time seismological monitoring station which is operational up to this day. The building is the work of a prominent Serbian Architect, Momir korunovich, and since 2007 it’s been on the list of Belgrade’s cultural heritage sites.

Tasmajdan Sculptures and Memorials

The park as it looks today (with only slight alterations) came to being in 1954. It spans between the Main Post Office on Takovska street and Beogradska steet on the other. Its adjunct, the so called Little Taš, continues even further towards Carnegy street. This bit of the park has the Faculy of Law and Hotel Metropol leanining on it, with the beautiful neoclassicist bulding of Serbian Archives and gargantuous, brutalist building of the Faculty of Technology in its surroundings. It is also a home to a petite gas station, loved by many fellow citizens who drive around the city center.

Tašmajdan’s form, conceived by A. Djordjevic and Radomir Stupar, is unusuly sensible example of a clear vision of urban development in Belgrade and it displays through consideration for needs of a potential future metropolitan area. Since then, it hasn’t changed much until its reconstruction in 2008. Then, to pretty much everyone’s surprise and random amazement, we saw some greater changes for the first time. The paths and running tracks (now covered in tartan) have stayed more or less the same, as well as most greenery and flower gardens, but the playgrounds were modernized, street lights were replaced, many old trees were cut down and gave way to a chess pavilion and an open/air gym. Moreover, a gaudy musical fountain was built on Beogradska street entrance. The pathways around it were paved in stone cubes and on the top of the fountain Belgraders have received two brand new monuments.

On the right side stands the statue of a damn fine and acclaimed writer, professor Milorad Pavich. His works have been translated in dozens of foreign languages, with Dictionary of Khazars still being widely read and re-read around the globe. On the more sinister side is the monument to a late leader of the glorious Azeri Nation, and the father of the current head of the state – Heydar Aliev. His name and cotribution to humanity are questionable, beyond the borders of Azerbaijan, and many Belgarder’s were baffled by it. It turned out that the contract that financed the restoration of the park stipulated its existenece. Namely after the oil boom, Azerbaijan has donated quite a bit of money all over the world and sculpture to the late president stands as a standard requirement to all of them.

Truth be told, the park has a long tradition of being an open air exhibition ground. Many works of the locally acclaimed sculptors became its full/time embellishments – i.e. Don Kihote, Golden Forest, Climber, Victory, Boar, Act, Slide and and Hub.

The park also hosts two other monuments that stand grim reminders to the gloomy history of Serbia. The first is the bronze cast, sitting figure of the children’s poet Desanka Maksimovic. In minds of those who attended primary school after the Second World War in the hilly Balkans, she is synonymous with her poem, A Bloody Fairytale, which was part of the school curriculum for a long time. The poem was dedicated to a group of high-schoolers killed during the Kragujevac massacre in 1941, and generations born in Socialist Yugoslavia know its verses by heart. The second monument, in spite of its dandellion shaped appearance, is also a morbid reminder to dead children. This one was built to honour the deaths of 81 children who killed during the NATO bombings in 1999. And there is an absurd and at the same time tragic story about it as well. The most prominent symbol of this monument was the statue of Milica Rakich, a three year old girl who was mortally wounded by a shrapnel of a NATO missile, while she was sitting on her potty in the bathroom of her family’s home in Batajnica. The majority of the people who saw the statue agreed that its authors have failed miserably in their intention. The face of the statue bore no resemblance to a face of a child, let alone the specific child it was supposed to represent, and it was downright spooky in our humble opinions. However, what ensued, illustrated just how bad the moral downfall of the Serbian society in late 20th century was – the statue was stolen, not long after it was put there, by bronze thieves.

Tasmajdan Stadium

The story of Taš would be incomplete without the story of its Stadium. The stadium was built in 1954, just behind the entrance to the quarry and under the cliff where the Chance stands today. At the time it was the central city stadium which hosted some significant sports events – Womens EuroBasket in 1954, Women’s Handball World Cup in 1957and Davis Cup in 1956.

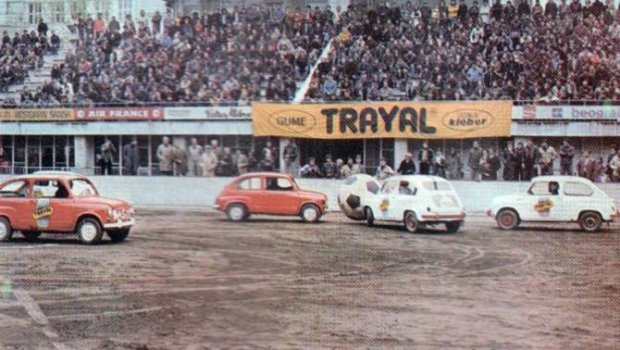

The court was mostly used as a practice ground for the basketbal players of Red Star and Partizan, and during wintertime it hosted hockey players and ice skaters. Balls, concerts and extravagant sports events (like the Spanish Corrida and the Autoball match in 1978) were also organized in Taš until the late 1980s.

In the early 1990s,however, it became completely defunct. The stands were crumbling away, and the dampness and neglect have deteriorated its interior to the point that it had constant flooding in the underground. It been a long time since anyone thought of hosting any kind of mass events, due to serious safety hazards. Finally in 2011, city authorities have begun its reconstruction. Those in charge of it said it would last till the end of that year. The year 2011, seems to have lasted for the past four years.

Tasmajdan Strawberry Tree

This concoction of absurd contrasts that Tašmajdan is wrought with, has a slightly brighter spot of a more recent date. Namely, 2011 was also the year when a small startup from Belgrade,called Strawberry energy, brought to fruition an idea of making renewable energy sources available to general public. These diligent innovators patented the first public solar mobile phone charger – first of which was planted in Tašmajdan Park. The Strawberry Tree, as the bench with a huge solar panel mounted on top of it is called, enables you to charge literally any mobile phone. Twelve different cables for different brands of phones clearly designated on both sides of the bench, and you can enjoy the view of the park while your phone is charging.

The trees are now present in more than a dozen cities, and since October 2015 they decorate the business hub of London – Canary Wharf. So where there’s a will, there’s a way. And it’s really hard not to feel proud of fellow compatriot ‘s achievements in this case.

Be First to Comment