Many stories have been told about Old Belgrade, but very few have been preserved in their entirety, either by their contemporaries or serious chroniclers. Particularly comprehensive ones are a proper rarity, very few were put on paper and almost none had been studied thoroughly. Proverbially negligent and destitute Serbia usually realizes the true value of its heritage once that heritage is gone. Because of all that, stories about Čubura may only be found in fragments, in the scarce memories of the elder citizens or the written endeavors of the very few enthusiasts who had bothered to scratch below the surface and leave a few lines for the future lovers of antiquities or historians.

The story of the Čubura Park is not particularly interesting if you leave out the story of the Old Belgrade or the story of kafanas in Čubura. Why, you might ask? Well, because park itself hasn’t got a particularly long tradition, or a sentimental value except for the generations born after the 1960s. Čubura park was cretaed two decades after the Second World War, as an attempt of urbanization and reorganizing of the neighborhood that has been undergoing a very visible, rapid change from the pre-war outskirt to becoming the part of the city core. The spirit of Čubura, in its Bohemian, prosaic sense is long gone and its true soul lies in the mud underneath the asphalt and just slightly flutters in the air above it. It is not surprising then, that it’s these few acres of the park and its immediate surroundings are today the closest that it gets to what should be considered Čubura from a random passersby point of view. Such view is not far from the truth either, as the park is a geometrical and social center of Čubura.

According to old Čuburians (or whatever the right way to call an inhabitant of Chubura is in English, translators remark), Crusaders (the inhabitants of Crveni Krst meaning Red cross) and inhabitants of Neimar (southern Čuburians), the area where the park is today is where the Čubura stream sprang. That is, right at the beginning of Čuburska street. It is considered that the name of the neighborhood is tied to the spring, although there are at least two versions of the story connected to it. Theory number one claims that the name probably stems from a Turkish word for self-filling pipelined stream, or a hollow barrel in the ground constructed so that it could be filled by clean water from a low pressure stream (basically a trough). It’s hard to say whether this translation is sensible, as Turkish linguists were scarce at the time of the writing of this article and the only translation of the word çubur that appears in online dictionaries is in Azerbaijani (which is an archaic version of Turkish) but it means snack or junk food (?!?). Speaking from experience, every attempt to check the meaning of (what we consider to be) Turkish loanwords with modern day Turks ends up with utter confusion and an inevitable Which word!? Never heard of it… On the other hand, every person convinced to know the meaning and the origin of the word will tell you something completely different.

The expanded theory goes on to say that Čubura used to be a Roma word for a tall barrel, as Roma people, were in fact autochtone to the area (for a long time it was nicknamed Harlem in slang toponymy). Another variant says that there used to be an abundance of summer savouries blossoming around the stream – as it’s pronounced čubra (chu-bra) in Serbian so the whole neighbourhood eventually got named after them. There are other, rather far fetched ideas like: the name stemmed from someone’s kubura (an Ottoman flintlock cavalry pistol, made predominantly in the Balkans and the Caucasus) or from an Italian suburre (meaning a slum), but those remain deep in the realm of random guessing.

As it is, nobody can tell with utmost certainty where it got its name, but one thing is for sure – the whole area is was permeated by water streams very much alike the Čubura stream. This spring, along with numerous others have filled the main bed of the large stream that flowed through the valley underneath Neimar and Čubura along the modern day Južni Bulevar. Across that stream looking to the far outskirt and the Dušanovac settlement, were the meadows, glades and roving huts. During the 1920s, when the area was modernized and the rapid growth of what was to be known as the city center thereof, Čubura stream was diverted into a rainwater drainage system and forgotten. It’s probably still ending its way in the largest of of all canals, somewhere near the E-75 freeway, and from there flows into the Sava. Many contemporary civil engineers learned the hard way that Vračar lies on a multitude of streams – as they had to battle phantom underground jets of water while they were laying foundations for their multi-storey apartment buildings.

The first step to proper urbanization of the space between Slavia and Crveni Krst was made by the much revered Scottish landowner and benefactor, Mr Fransis McKenzie. In 1887 he bought the land between Slavia and Vrachar Plateau, or the bit that is today boredred by the Bulevar Oslobođenja and Njegosheva street. He was the first to drain this piece of land and parcel the glades, reeds and wild hunting grounds of the outskirts into city parcels, which were then sold to the artisans and craftsmen who were flooding into Belgrade. Later on, he donated the land for the construction of the Saint Sava Temple. MacKenzie was also the reason why the area above Slavia was nicknamed Englishtown, which, untill the second half of the twentieth century was known as a workers’ and artisan’s neighbourhood.

The golden age of Serbian kafanas kicked off at the end of the 19th century alongside with the process of turning a hinterland smalltown into a serious city. in it, Chubura developed into a settlement with its own identity, so strong that it became part of an urban myth – one that is gradually, but certainly fading away from the collective memory of the city

According to some sources, Belgrade was the first city in Europe to have a kafana back in 1522. They only served Turkish coffe, tobacco and sitting took place on its floor. In the centuries that followed, kafanas have pretty much shaped Belgrade’s

identity, and their glory and institutionalisation started from 19th century onwards. They were the true social network of their times. They served as gathering spots, theatres, concert halls and literary associations hubs. Business deals were made there, people networked and gossiped, lived and dided in them. Kafanas were the central nervous system of Belgrade, until a bit after the WWII. What happened to Belgrade, applied to Vrachar and Čubura as well.

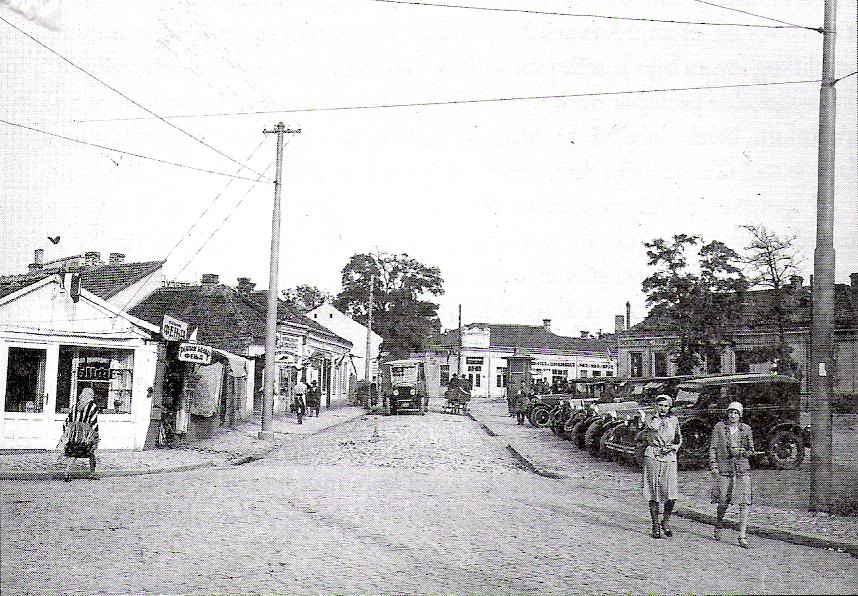

Then, a new era ensued. After the war, the shabby huts of Vrachar disappeared one after another. To make space for the park, a block of shacks and lop sided ruins, once so charateristic of Bekgrade was pulled down. There used to be a small world nested between Orlovicha Pavla, Maxim Gorky and Chuburska street: a Roma settlement with hundreds of inhabitants had vanished and so did the old family houses together with the legendary Kikevac which used too stand at the conmer of Emperor Nikolay (previously 14 december) and Maxim Gorky (previously Prince Peters). At the opposite corner, right at the beginning of Chuburska street, proudly stood the old Chubura. It managed to survive, albeit in the form of its younger namesake in Peyton Place. The one today is a reputable kafana, but they say that no copy can be as good as the original.

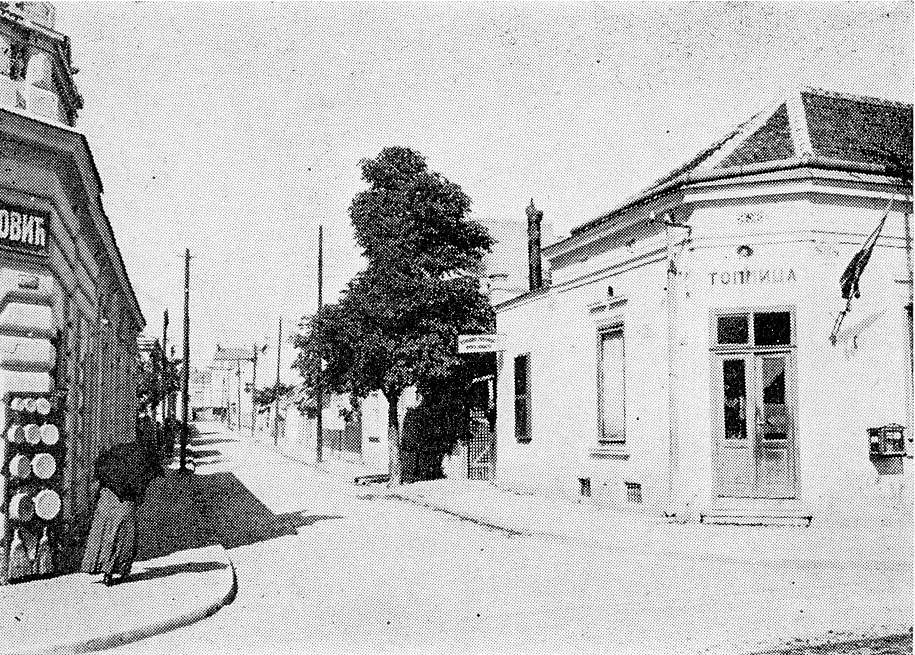

A few neighbouring kafanas are also worth metioning, as the legend of Chubura would not exist without them. Less than hundred meters away, below the park, is still home to Sokolac and further down the street is the Old Serbia. Sokolac was the place of the elite – the wealthier and slightly more educated Vracharians from the ones in Kikevac and Chubura used to hang out there. This list should also contain Trandafilovich , (at the corner of Mckenzy’s and Mutaps), Toplitza at the corner of Mackesies and Ivana Djaye street which is now home to The Ploghman (Orach). There was also a New Belgrade, in Mackenzies, Kalenich at the far end of Mileshevska and so on…

It is said that in the period between the two world wars, Kikevac had a famous “tennant” a certain Atza Big Nose. It was said that he didn-t have a home, and that he slept on chairs in the kafana and entertained guests, who would in retrn buy him a round. Čubura had a great many stories and destinies of that sort to tell. What happened in kafanas, was in its own right a “reality show” for the locals and those into kafana events…far more humane than the ones we see on TV today.

The list of famous Čuburians, to the best of our knowledge is pretty much restricted to the ex-Yugoslav boundaries. One of them was Petar Kočić, who, during his tenure in Belgrade, frequented the kafanas in the neighbourhood, and his statue stands proud in the middle of the park today.

A great many of elder living Čuburians have certainly spent some time in kafanas in Chubura, if only in their childhood, because that was the way of life back then. The most famous among the most frequent visitors of those kafanas was definitely Libero Marconi – Slobodan Markovich, a famous poet, painter and a raving alcoholic whose drunken stunts were as impressive as his poetry. He lived and loved Čubura and honestly was not particularly pleased with the park. In a preface to an interview he did with the shopkeepers from Peyton Place in 1974, he commented that

“that sacred place where the bass strings resounded up in heaven was erased…and a so called park put in its place, where the main institution is the public toilet.

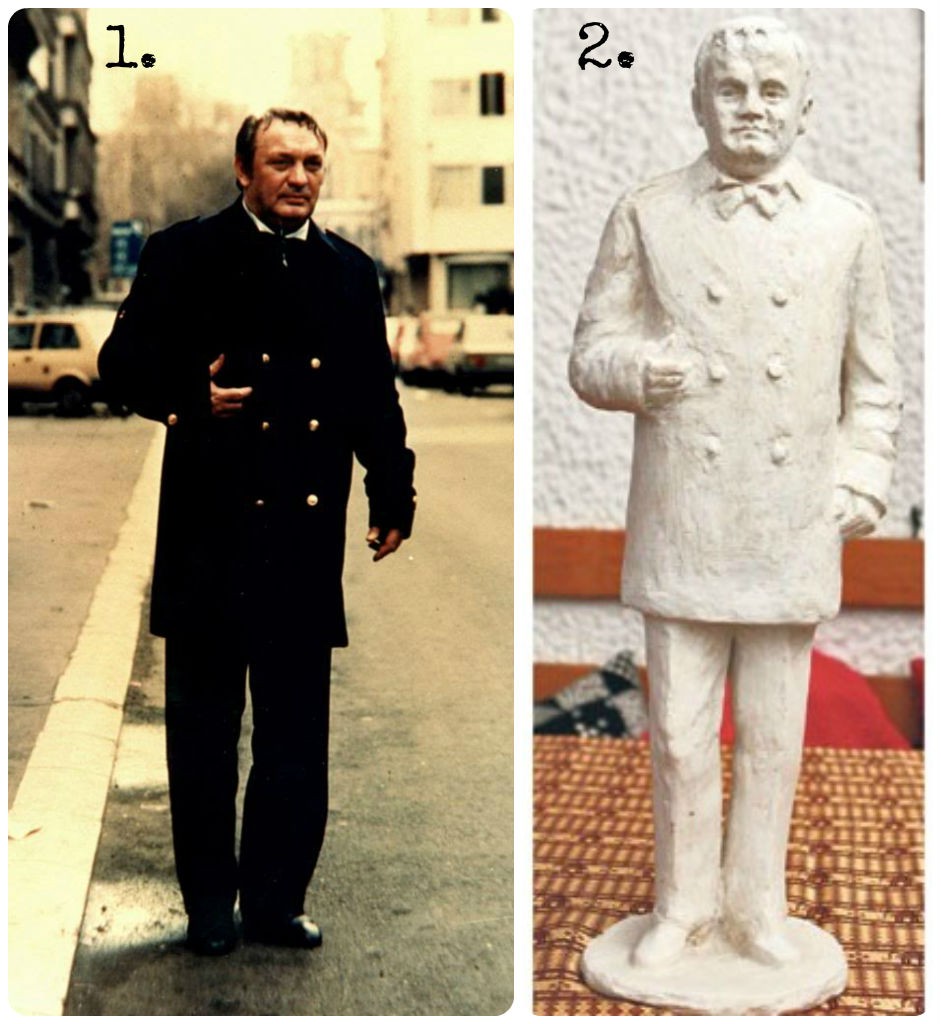

Ironically, he seems to be the next in line to get monument in that very park. The city authorities are pretty close to giving a green light to Ms Drinka Radovanović, a naive artist who also resides in Čubura. His closest family, however, seems to be opposed to the choice, as they claim that the sculptor has turned Libero into a sick, disproportionate infant with a face of an old man. We’ll let the readers be judges of that:

2. A proposition for a monument- expressionism “par excel lance”

Others famous people from the neighbourhood, but pretty much restriced to ex Yugoslavia, include Bata Zhivojinovich (a man whose movie character has a beer named after in China), Dragan Nikolich, Olivera Katarina , basketballers Duda and Piva Ivkovic, academic painter and a naive writer (renown for his writing) Momo Kapor, Zoran Hristic, Dushan Prelevic, Jovan Joca Ristic and others

Čubura Park today is a neat and orderly spot and an all time favorite of local kids. A few years back, it also got a skate park. Basketball hoops have been there for at least thirty years, as witnessed by the author of this text. Čubura park also boasts two playgrounds (one for kids and one for pets) and a fresh water tap (that had not been operational during my last visit on a scorching day in the middle of the summer). In author’s humble, local-patriot, opinion it’s in a right spot, and appears that its planners have actually done a pretty good job. As planning is not a habitual course of action in this part of the world, it would be nice to have it as a rule, rather than an exception.

Therefore, if we had to kill a tradition to get the park, may the park then, become a seed of a new tradition, of using our brains, and may it uproot in coming decades.

Be First to Comment